Hyperspectral Imaging

Introduction

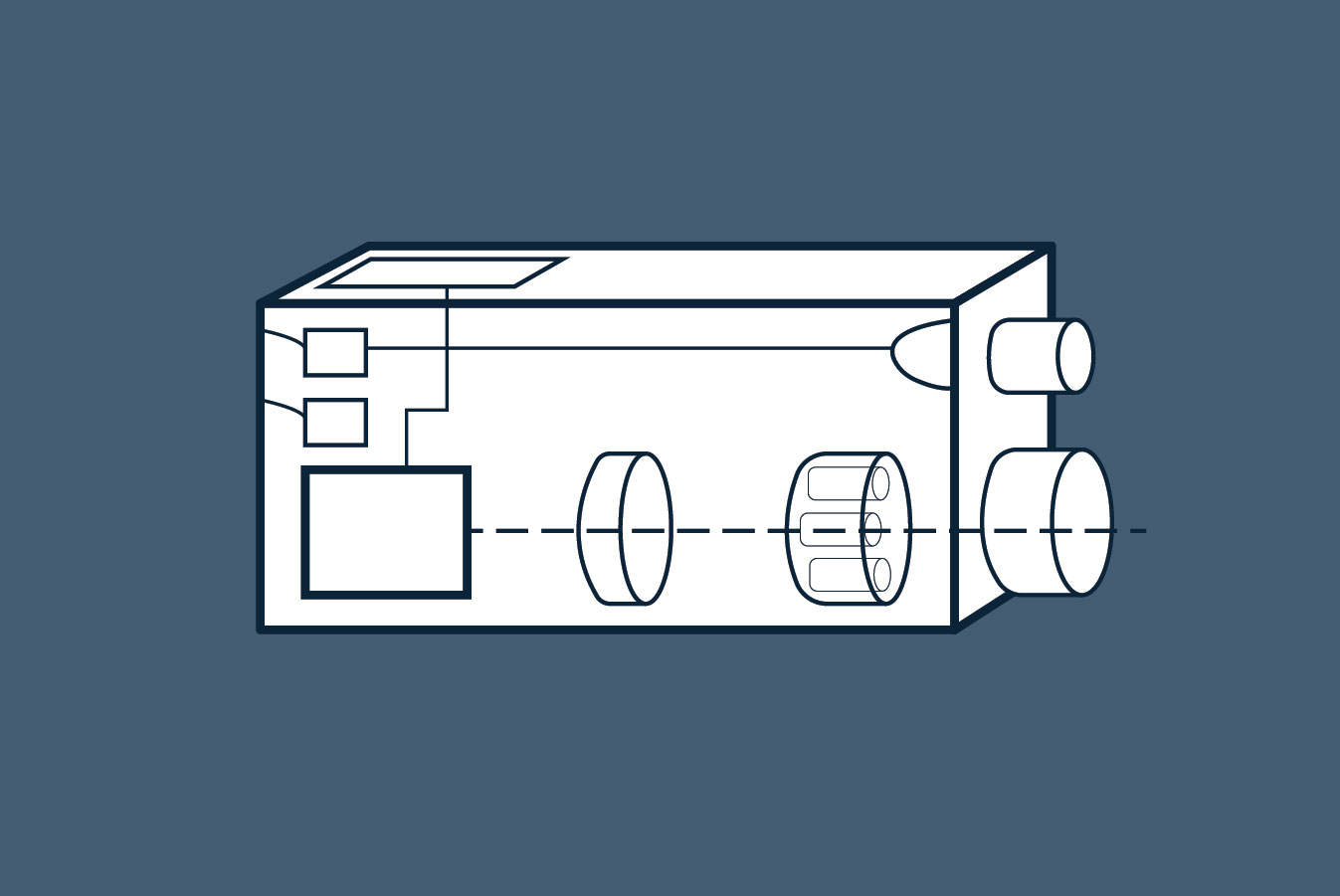

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is a type of remote sensing that takes a series of hundreds or thousands of contiguous images in narrow wavebands across the visible and infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. This allows hyperspectral imaging to capture more data about its target than conventional color photography, which only takes images in the red, green and blue segments of the visible light spectrum. The series of images captured by hyperspectral sensors forms a “hyperspectral cube” that contains detailed spectral information about each pixel in the image. HSI can take advantage of differences in the way that materials reflect light (forming unique spectral signatures) to identify the materials present in an image, aiding in the detection of decoys and other camouflaged targets.1

Successfully using HSI to find and identify items of interest requires the ability to process an extremely large amount of gathered spectral information to locate the small number of pixels possessing characteristics of interest and subject them to further scrutiny.2 Effectively carrying out this analysis relies on the possession of a large library of the spectral signatures of materials ranging from leaves in various stages of health to vehicles, camo-patterns, and countermeasures.3

HSI data can be processed in two ways: anomaly detection and signature-based detection. Anomaly detection identifies spectral deviations from the background and subjects them to further analysis, whereas signature-based detection searches large areas for objects possessing a certain known spectral signature.4 In either case, this already complicated and computing-power intensive task is made more difficult by the need to correct for atmospheric absorption and scattering, the effects of which vary depending on the distance from the target and the weather at the time of information collection. Additionally, due to an inherent level of spectral ambiguity in the field, collected spectral signatures can vary from the information recorded for that material in the spectral library.5

Finally, significant complication arises from the interplay between the spatial resolution of the sensor (the amount of space represented in one pixel) and the spatial variability of the ground area being imaged.6 The sensor integrates the spectral information from all materials in the ground area defined by the spatial resolution into a single image pixel. If the spatial resolution is low and the target ground area is highly variable in composition, the resulting images will contain a high number of mixed pixels, which can present an additional challenge to analysis because their spectral signature will not correspond to any single well-defined material.

As HSI sensors become more powerful, their increasing spatial and spectral resolution will help to overcome these problems, enabling more effective material discrimination and thus target identification at an increasing range. However, increases in the precision of the sensor are accompanied by increases in the volume of the data generated, resulting in increased bandwidth and computing power requirements to transfer and effectively analyze it. As a rule of thumb, commercial HSI generated about 1TB of data per hour of footage.7 Recent advances in the theoretical and algorithmic approaches to target identification, spectral unmixing, and anomaly detection, coupled with developments in machine learning, have increased the speed and efficiency of sorting and interpreting the massive quantities of data, increasingly allowing HSI to provide time-sensitive intelligence analysis.8

Hyperspectral sensors can be deployed on a variety of platforms, including satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). Hyperspectral sensors deployed on satellites and UAVs are typically passive sensors that rely on reflected sunlight to take images. Sensors deployed on UUVs that operate in the deep-sea need to actively illuminate their subject in order to take images.9 Both passive and active sensors have drawbacks. Passive hyperspectral sensors’ operations may be hindered by bad weather and darkness. Active hyperspectral sensors can operate in darkness, but their light source may give away their presence to adversaries.

-

Peter WT Yuen and Mark Richardson, “An introduction to hyperspectral imaging and its application for security, surveillance, and target acquisition,” The Imaging Science Journal 58, no. 5 (2010): 241-242. ↩

-

“Hyperspectral analysis set to expand in coming decade,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, June 23, 2017, http://www.janes.com/images/assets/127/72127/Hyperspectral_analysis_set_to_expand_in_coming_decade.pdf, 4. ↩

-

Ibid., 249. ↩

-

Xavier Briottet et al., “Military applications of Hyperspectral Imagery,” Wendell R. Watkind and Dieter Clement, eds., Targets and Backgrounds XII: Characterization and Representation 6239, International Society for Optics and Photonics (2006): 62390B, publications.tno.nl/publication/34617027/4SzPMU/briottet-2006-military.pdf. ↩

-

Yeun and Richardson, 249. ↩

-

Briottet et al. ↩

-

“Hyperspectral analysis set to expand in coming decade,” 4. ↩

-

“Hyperspectral analysis set to expand in coming decade,” 5. ↩

-

“Underwater Hyperspectral Imaging reveals the secrets of the sea,” Specim, March 4, 2016, http://www.specim.fi/revealing-the-secrets-of-the-sea/. ↩