Understanding Situational Awareness Technologies and the Emerging Situational Awareness Ecosystem

The rapid expansion of new and existing technologies can provide opportunities for major breakthroughs in the ability to detect threats; track hostile actions and forces; process, interpret and communicate vast data sets; and predict and shape the actions and possibly even decisions of adversaries. Every technology has costs and benefits associated with its adoption, and the capabilities in the emerging strategic SA ecosystem are no different. Each of the emerging capabilities explored over the course of this project can be described using two separate categories: attributes for increasing strategic SA (discussed in this chapter) and risk factors that decrease strategic stability (addressed in the next chapter).

Platforms, Critical Enablers, and Defense and Counter Capabilities

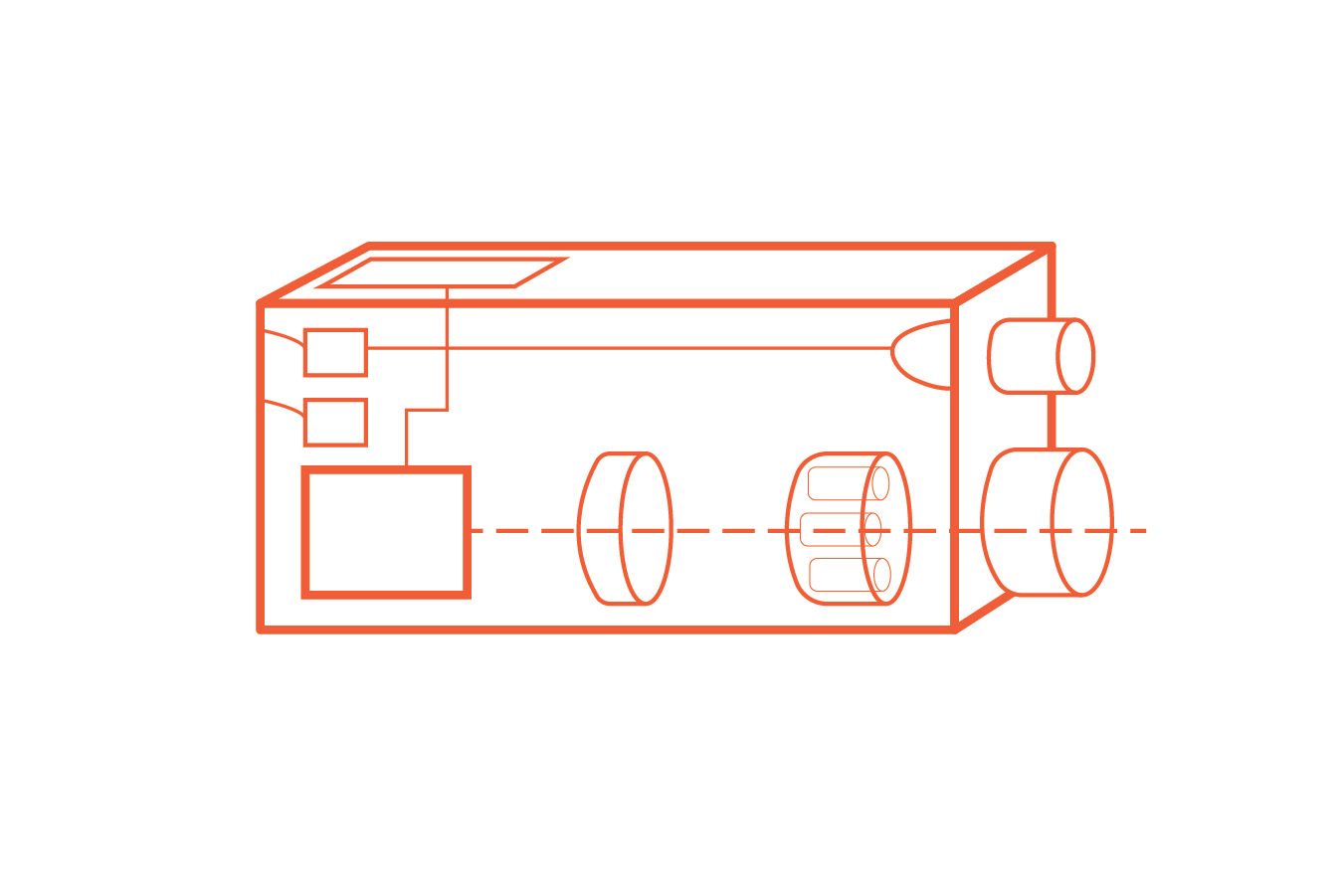

The new technologies that will shape the strategic SA ecosystem moving forward can be divided into several broad categories. For the purposes of understanding and analyzing SA technologies and their effect on strategic stability, this study draws a distinction between “platforms” and “critical enablers.” “Platforms,” such as satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), or even microchip-enabled proximity cards, are the physical systems or structures necessary to access a collection target, carry a variety of sensor payloads, and support communications and data transmission from the sensor package. “Critical enablers,” on the other hand, are the sensors, applications, or other technologies used to collect or analyze SA data many of which can be used on or in support of a variety of platforms. In the examples above, these would be the sensors attached to a UAV or the digital applications which collect and analyze data collected by those sensors. Technological advancement and innovation have been key to the development of both platforms and critical enablers. For example, advances in miniaturization, autonomy, robotics, and other technologies have led to the development of platforms that are smaller, more mobile and agile, and harder to detect. To better analyze the individual technology and the costs and benefits associated with employing it, platforms and critical enablers may be treated as a distinct for academic or theoretical purposes. However, in real-world scenarios, a critical enabler is useful only after its marriage with a platform that can put it into position to gather and process desired information.

Finally, in addition to platforms and critical enablers, this project also explored some strategic SA capabilities that may be termed “defense” or “countering.” These capabilities contribute to the strategic SA ecosystem differently than most platform-critical enabler combinations: whereas most strategic SA capabilities focus on collecting information that can be used to inform decisionmakers during crisis or conflict, defense and countering capabilities either defend against adversary activities (for example, cognitive electronic warfare systems tasked with detecting, suppressing, and neutralizing adversary cyber intrusions) or seek to counter or degrade an adversary’s strategic SA (such as through spoofing activities that can obfuscate an adversary’s ability to perceive the operating environment). Together, defense and countering capabilities account for a small number of capabilities explored during this project, but such technologies may play an outsized role in escalation dynamics during future crises or conflicts given their potentially destructive nature and relevance to gray zone tactics.1

-

Melissa Dalton et al., By Other Means Part II: Adapting to Compete in the Gray Zone (Washington, DC: CSIS, August 2019), https://www.csis.org/analysis/other-means-part-ii-adapting-compete-gray-zone. ↩